Stroking Characters

Chapter 7 of the Wenlin User’s Guide

Chapter 7 of the Wenlin User’s Guide

This chapter describes Wenlin’s stroking box and explains general principles of writing Chinese characters.

If you can write a character using Wenlin’s standard stroke order, then you can use the ![]() brush tool to input characters, as described in Chapter 4.

brush tool to input characters, as described in Chapter 4.

Contents

Calligraphy

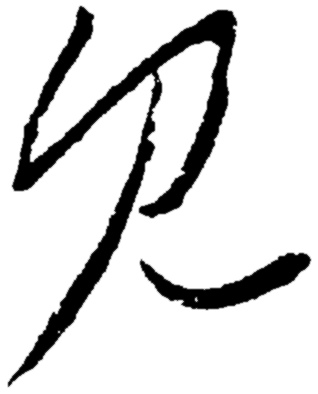

见 jiàn ‘to see’ – as written by 王羲之 Wáng Xīzhī (fourth century)

Calligraphy is the art of beautiful writing. Its origins can be traced back thousands of years to the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty, but it was improvements in various materials such as brushes, inks, silks and papers, about two thousand years ago, that fully enabled artistic expression. Using a brush, a calligrapher can carefully regulate the pressure, thereby controlling the thickness of each part of the stroke. An infinite range of expression is possible. Well-written characters are vital, rhythmic, balanced and harmonious; above all, they are alive.

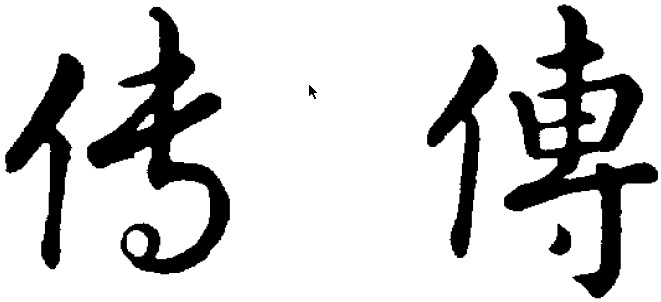

传(傳) Chuán ‘pass on (tradition)’ – as written by 宋高踪 Emperor Sòng Gāozōng (twelfth century) in grass script (left) and regular script (right)

The Stroking Box is Not Calligraphy

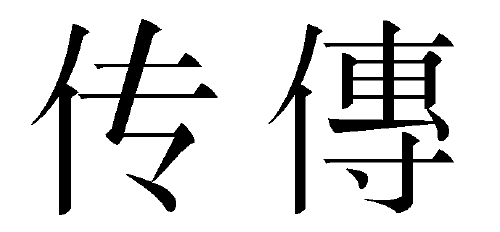

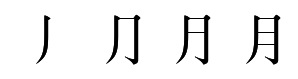

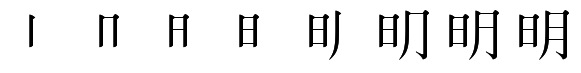

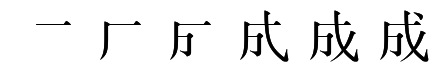

Wenlin uses its CDL (Character Description Language) font for the stroking box:

The CDL font is computer-generated, and not as beautiful or interesting as what a calligrapher can produce with a brush. It’s based on a printed style that became popular in the Song dynasty (960-1279), following the invention of woodblock printing. This “Song” style does to some extent imitate the variations in thickness that can be made with a brush, but the overall effect is of straight lines and sharp corners, revealing the influence of the knife used to cut the wood. Horizontal strokes are thin and have bumps on the right ends. This is the style most often seen in modern print, long after the age of woodblock printing.

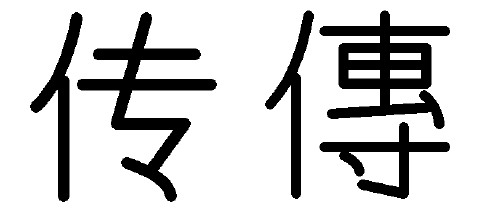

The CDL font also supports a “plain” style:

Since you can’t really imitate the ornamentation of the Song style with a pen or brush, and since you probably won’t be using a knife to carve characters, you might sometimes prefer to use the plain style as a guide. However, the Song style looks so much better that we made it the default. Depending on the limitations on our skill, time, and technology, future editions of Wenlin may have calligraphic characters in the stroking box, recording the strokes of a human hand. For now, we have concentrated on legibility, speed, quantity, and utility. The stroking box can display about eighty thousand (80,000) characters stroke-by-stroke.

In a sense, the strokes in the stroking box are analogous to musical notation: just as musicians bring written notes to life by playing them with feeling on real instruments, you can bring characters to life by writing them with feeling on real paper.

The Stroking Box

With the stroking box, you can see an animated display of how to write a character. By following along with a pen or pencil, you’ll learn stroke order.

The stroking box can be accessed two ways:

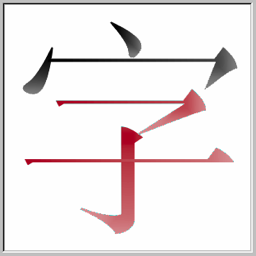

- 1. Through ▷stroke buttons in the Zìdiǎn dictionary entries of individual characters.

- 2. By pressing the space bar when a Zìdiǎn entry is displayed.

To access the stroking box and see how to write a particular character:

- • Open up the character’s Zìdiǎn entry (click on the character)

- The dictionary entry opens, and it contains a ▷stroke button

- • Click on the ▷stroke button (or press the space bar)

- The stroking box appears

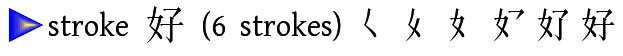

For example, inside the dictionary entry of 好 you’ll find:

Press the triangle button, and the stroking box appears in its own window.

There are four buttons you can use for stroking the character: ![]()

- To see the entire character written automatically, press this button

or press the Return or Enter key.

or press the Return or Enter key.

- To initiate each individual stroke, press this button

or press the space bar; then, with your free hand, you can write the character on paper.

or press the space bar; then, with your free hand, you can write the character on paper.

- By pressing this button

, you can “back up” or “undo” a stroke. This is occasionally useful if the character has many strokes, and you realize in the middle that you want to go back a stroke or two to clarify the order, or to clarify the direction of a single stroke.

, you can “back up” or “undo” a stroke. This is occasionally useful if the character has many strokes, and you realize in the middle that you want to go back a stroke or two to clarify the order, or to clarify the direction of a single stroke.

There are also controls for changing the speed (note: màn 慢 means slow and kuài 快 means fast), choosing foreground and background colors, and changing the thickness of strokes.

- Checking the red radical checkbox colors the Radical portion of the character red. (In the above illustration, the strokes of the 子 ‘child’ component constitute the 6 red radical strokes, while the 宀 ‘roof’ component gives the 3 blue residual strokes.)

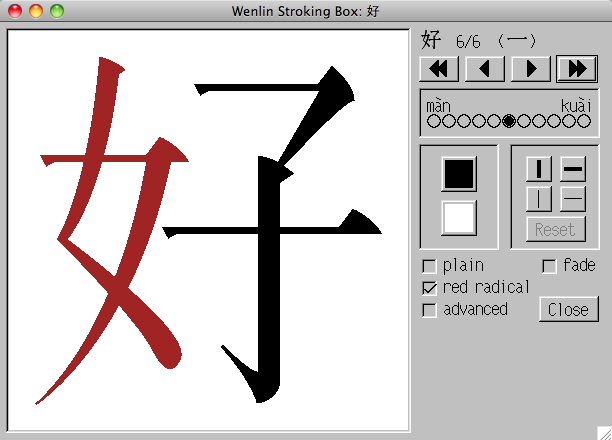

- Checking the fade checkbox applies a textured fading colorization (not shown above) to the strokes of the character. The following image shows the fade effect.

(CDL for 字, red radical option on)

When you are finished with the stroking box, click on the Close button, or press the Escape key.

You can stroke both simple and full form characters. For example, the simple form of jiàn ‘see’ has this button in its dictionary entry:

and the full form dictionary entry has this button:

When you have opened the entry of a simple form character, you can open the full form entry by clicking on the full form where it appears in parentheses on the top line; and vice-versa.

There is an advanced checkbox that only appears in the stroking box if Enable advanced CDL (Character Description Language) features has been turned on under Advanced Options in the Options menu. The appendix on Character Description Language has more information.

Principles of Stroke Order

It is helpful to think of each Chinese character as standing calmly inside an imaginary square. The individual strokes that form a character can be long or short and they can reside at any location within this square. Roughly speaking, a stroke is any line or curve that is written without lifting the pen off the paper. The total number of strokes needed to write a character is called its stroke count.

The overall direction of writing is from top to bottom. Historically, the characters have usually been written in columns, and the columns flow from right to left. Yet the strokes in a single character are generally written from left to right, probably because most people are right handed, so the current stroke is not covered by the hand, and previous strokes are visible. Why the columns go from right to left is not clear. Modern writing is often in rows, from left to right just like English.

Although a character may have ten, twenty or even thirty strokes, each stroke should be written in the proper order. The stroke order is based on general principles that, when followed, produce beautiful and balanced characters. Even though different dictionaries disagree slightly on the stroke order or stroke count of some characters, the following principles are well established.

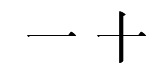

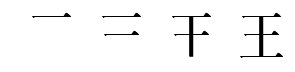

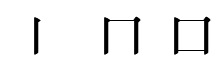

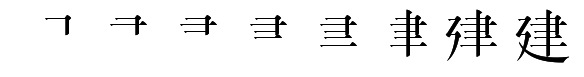

1. Begin at the left and proceed to the right.

2. Begin at the top and proceed to the bottom.

The combined effect of the first two rules is a tendency to begin at the top-left corner and proceed to the bottom-right corner.

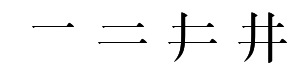

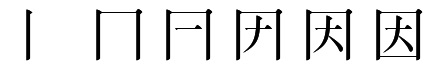

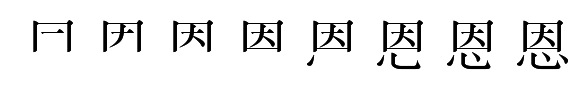

3. Begin with the outside and proceed to the inside.

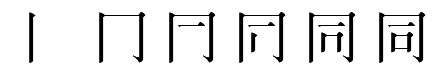

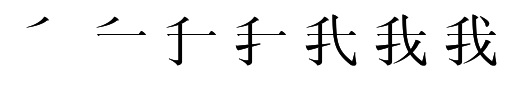

4. When two or more strokes cross, write horizontal strokes first.

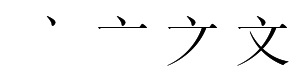

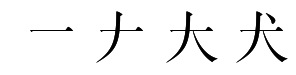

5. Write a left-slanting stroke before a right-slanting stroke.

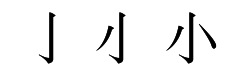

6. The following is an exception, in which the vertical stroke should be written before the penultimate horizontal stroke:

7. Write a center vertical stroke before symmetrical wings.

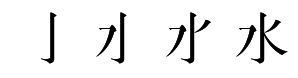

8. Write a box with three strokes. If anything goes inside the box, write the first two strokes; then write the contents of the box; finally, complete the box.

9. If there is a dot in the top-right corner, write it last.

10. If a character is composed of two or more components, write the components individually (left to right if they are arranged horizontally, or top to bottom if they are arranged vertically), and preserve the stroke order of each component. The stroke order of a new composite character is generally easy to figure out if you know how to write its components.

11. For the components 辶 and 廴, apply the “top to bottom” rule rather than “left to right” – so write them last.

(Note: the “top to bottom” rule does not apply to similar but more complex components such as 走 in 起, and 是 in 题, for which the rule is “left to right”.)

12. These rules are widely applicable. However, sometimes two rules seem applicable to the same character, and contradictory! The final rule is, when in doubt, consult Wenlin.

How Standard is the Standard Stroke Order?

The primary authority for the shapes of Chinese characters in Wenlin, including stroke count, stroke order, and classification according to stroke types, is a book entitled 现代汉语通用字笔顺规范 Xiàndài Hànyǔ Tōngyòngzì Bǐshùn Guīfàn (Yuwen Chubanshe, Beijing 1997, ISBN 7-80126-201-8). It was compiled by the National Spoken and Written Language Work Committee and the Standardization Work Committee, and includes 7,000 simple form characters. It’s almost entirely consistent with earlier PRC publications (such as 汉字正字手册 Hànzì Zhèngzì Shǒucè, 1985). Since the book does not specify stroke orders for full form characters that have different simple forms, in some cases it was necessary to refer to other authorities to decide the full form stroke orders.

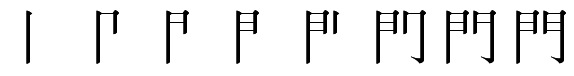

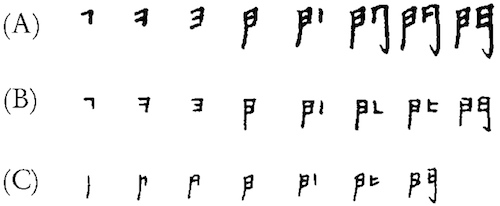

One of the least agreed upon stroke orders is that of the full form character 門(门) mén ‘door’:

This order agrees with all of the following sources: 《常用國字標準字體筆順手冊》 (教育部國語推行委員會編輯, 1996; ISBN: 957-00-7082-X); Reading & Writing Chinese by William McNaughton; China: Empire of Living Symbols by Cecilia Lindqvist; and Essential Kanji by P.G. O’Neill. It is just like 朋 péng ‘friend’.

But this order disagrees with the following: (A) Learn to Write Chinese Characters by Johan Björkstén; (B) Mandarin Primer by Yuen Ren Chao; and (C) Read And Write Chinese by Rita Mei-Wah Choy.

For composite characters, the stroke order is implicitly determined when: (1) the character can be clearly divided into two or more graphical components; (2) the order in which to write the components is clear; and (3) the stroke orders of the individual components are known. For example, having decided on the stroke orders of 門 and 耳, there is no longer any doubt about the order of 聞. Internally, Wenlin stores the shapes of compound characters in terms of their components, rather than building each character up separately out of individual strokes. This method leads, quite naturally, to consistent stroke order information.

Reasons to Learn a Standard Stroke Order

- Chinese characters are beautiful, and writing them is pleasurable. To write them well, you are far better off learning a set of guiding principles than operating in a vacuum.

- Writing by hand, over and over and over, with a consistent stroke order, helps you memorize characters.

- When you learn stroking principles, you simultaneously learn how to use Chinese dictionaries. Many dictionaries index characters according to stroke count, stroke type and stroke order.

- You also learn how to take advantage of Wenlin’s lists of characters by stroke count and stroke order, as explained in Chapter 6. This is a good way of looking up a character when you don’t know its pronunciation.

- If you write with Wenlin’s standard stroke count and stroke order, you can use the

brush tool to input characters and look them up.

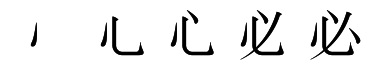

brush tool to input characters and look them up. - A knowledge of stroke order can help you decipher handwriting. For example, 口 kǒu ‘mouth’ is often written like this:

It doesn’t look very much like a square. The three strokes are joined into a single stroke. Nevertheless, you can see that it follows the standard stroke order: first the left side, then the top and right sides, finally the bottom. Otherwise, it would be completely illegible.

![]() | Previous: 6. Lists | Next: 8. Editing Documents | Contents |

| Previous: 6. Lists | Next: 8. Editing Documents | Contents |